Next America 4: Did We Decide to be a Graying Church?

Section Summary

My enthusiasm for The Next America has been renewed after reading Chapter 4. It was full of insights I would not have gained without this book. For one thing, I had not sufficiently considered the impact of longer lifespans:

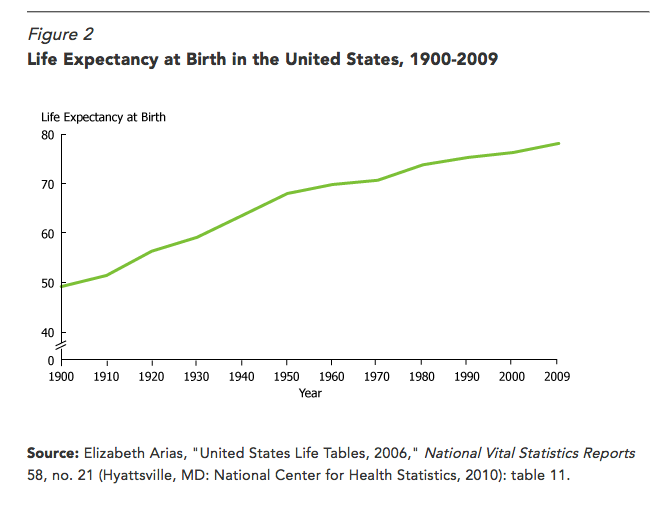

In 1900, with significant infant and child mortality, life expectancy at birth was a mere 47 years old. By 1950, life expectancy at birth was closer to 70 years old, a significant gain. And by 2009, lifespan at birth was almost 80 years old. Combine that with a post World War II baby boom and what do you get?

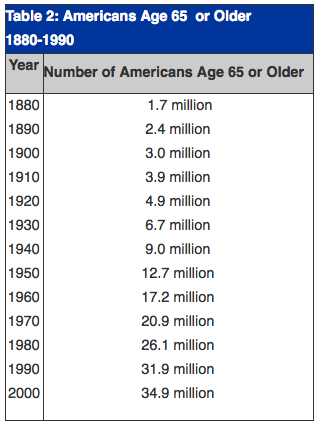

You get a large population of individuals over age 65. In fact, the US population contains almost triple the adults over age 65 in 2000 than existed in 1950. That has an impact on generational life:

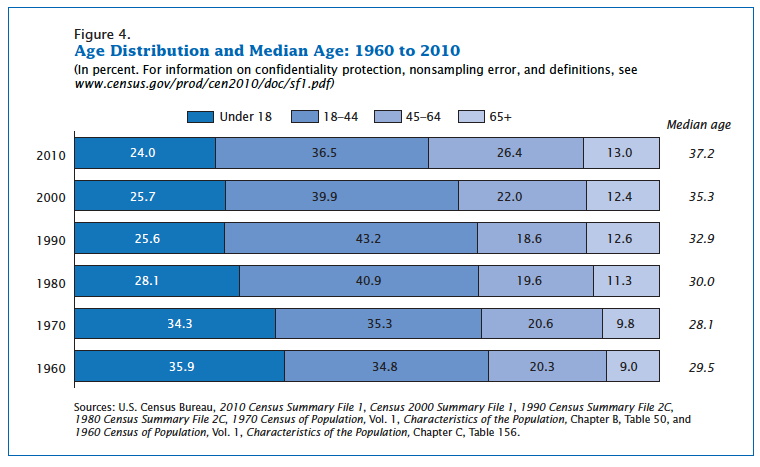

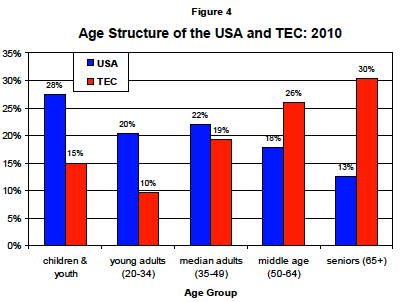

In 1960, only 29% of the population was over age 45 and more than a third under age 18. In 2010, almost 40% of the population was over age 45, and less than a quarter under age 18. It’s not just that the church is getting older; all America is getting older. (The church is graying faster than the rest of America; more on that after the summary.)

In 1960, only 29% of the population was over age 45 and more than a third under age 18. In 2010, almost 40% of the population was over age 45, and less than a quarter under age 18. It’s not just that the church is getting older; all America is getting older. (The church is graying faster than the rest of America; more on that after the summary.)

The above graphs make the main point of Chapter 4 clear. From p 45-45:

The unsparing arithmetic of a graying population is about to force political leaders to rewrite the social contract between young and old. This will lead to tax increases, benefit cuts, or both… The federal government now spends nearly $7 per capita on programs for seniors for every $1 it spends per capita on programs for children. But even as spending priorities have migrated toward the top of the age pyramid, economic need has settled toward the bottom.

Much of this chapter is about federal budget policy and the demographics of a graying population, both in the United States and globally. The focus is on public opinion about public benefit programs:

- Most Millenials and Gen Xers say Social Security needs major changes or a complete overhaul, while most in the Silent Generation say the system works pretty well.

- The public favors keeping entitlement benefits as they are over reducing the budget deficit by 58% to 35%.

- Expectations about Social Security vary across generations: in the Silent Generation, 58% cite the program as providing their main source of retirement income, while 72% of Millennials don’t expect the same for themselves.

- Those who depend on Social Security (or expect to) overwhelmingly favor maintaining the program, while those who don’t now and/or don’t think they will in the future favor deficit reduction instead.

The final takeaway, which has major implications for the church:

Come the inevitable day when entitlement programs for seniors are trimmed, families will have to reclaim some of the caregiving ground they’ve surrendered to the state. These challenges will be daunting, because the architecture of the American family has changed dramatically since presidents Roosevelt and Johnson built these programs…

Churchwork Reflections

Since I’m reading this book with an eye to the church’s future (and not as a public policy analyst), I was struck by the demographic shifts themselves far more than their implications for Social Security and Medicare. That’s why I went and found those lovely charts above.

Those of us in the mainline churches tend to feel nostalgic for the days when children and youth were filling our buildings. Even though I didn’t join a church until 1991, missing the moment entirely, I still find myself afflicted by this disabling emotion. This chapter helped me realize that these buildings full of kids didn’t just occur because the church was doing an extraordinary job articulating and living God’s mission (although that might have happened also). Rather, it was simple math: there were a LOT more children and youth as a percentage of the population.

The population of America has become grayer overall, with the average age creeping up from 29.5 in 1960 to 37.2 in 2010 (see the Age Distribution and Median Age chart above). Meanwhile, the Episcopal Church has rushed the trend, with a larger proportion of older adults than the general population:

And the Episcopal Church isn’t alone: the 2008 Faith Communities Today survey found that in sixty percent of mainline denominations, one-quarter of the members are 65 or older.

How many of these older adults joined a church in the “boom years” and simply never left? This question isn’t raised in Faith Communities Today. But the Episcopal Overview: FACT 2010 report (available to download here) does state that 18% of all Episcopal Churches were founded between 1946 and 1965: the Baby Boom years. If almost a fifth of our churches were founded during the Baby Boom, what implication might that have for the number which can survive current smaller birthrates?

From Reflection to Action

In order to make disciples in younger generations, the church cannot rely on demographic trends and cultural support. We must be intentional and strategic about allocating resources to ministry with children, youth, and young adults.

It was recently reported that the international Episcopal Church has received pledges of $26.8 million for 2014. How many of those dollars will go toward ministry with the 24% of the population under age 18?

The 2013-2015 budget allocates $2.8 million for the entire triennium for “Formation and Vocation” (lines 63 to 70, which include all our ministry with people aged 0 – 22). That means that in a single budget year there is less than $1 million for this work. Not even 3% of the resources available for ministry on the churchwide level are being allocated to reach more than 24% of the population. And we wonder why we are a graying church?

Throwing money at problems doesn’t solve them, but we can’t structure for discipleship without sufficient resources.

So today my action step is asking you this question:

Is it possible that we in the Episcopal Church have demographic issues that mirror the larger society: the favored projects of the older generation are receiving outsized resources at the expense of ministry with future generations?

Member discussion