The Gift of Data (Part 5)

This is the fifth post in a series. You can read the first four posts here.

This is the fifth post in a series. You can read the first four posts here.

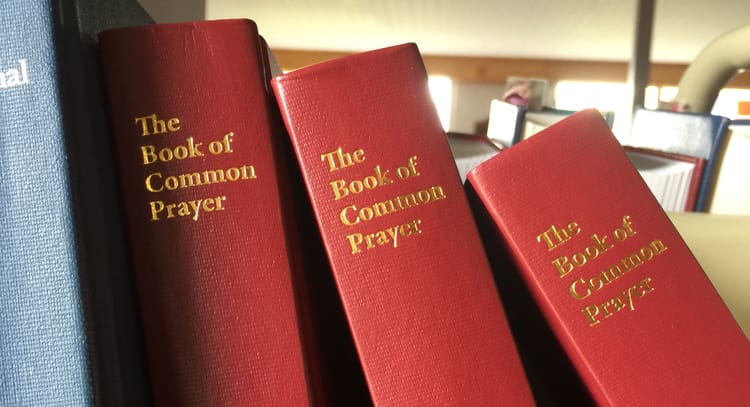

In my last post, I shared some depressing data: my diocese of the Episcopal Church has not kept up with population growth. In the last hundred years or so, the Episcopal Church has gone from being about 1 in every 100 people to fewer than 1 in every 200. {Heavy sigh.} That’s some depressing data.

And, let’s face it: these days, Christians usually find church population data depressing. (I’m sure it cheers up atheists.) I think that’s one of the reasons we don’t talk about it much.

It was probably fun to discuss church data in the 1950’s (or whatever era it was, before I was born, when the church actually grew) but lately, it seems to be a total downer. And people avoid dealing with total downers. Some of us call that denial. (We still avoid downers, but we know how to describe our avoidance. Doesn’t that count? No? Oh well…)

But no matter how much we avoid it, the (depressing) data is there. And we have to care about data because in the church, data means people. When we avoid dealing with data, we avoid our mission: to love our neighbor, to make disciples.

So, how do we handle data that is depressing? What about the dreaded Triple D – deeply depressing data?

By greeting it with two equally important, somewhat paradoxical attitudes: holy indifference and passionate curiosity.

On the one hand, holy indifference. This is the attitude expressed by St. Paul when he said, “If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord; so then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s.” (Romans 14:8). It is the attitude expressed by St. Theresa when she said,

Let nothing disturb you, let nothing frighten you. All things are passing away: God never changes. Patience obtains all things. Whoever has God lacks nothing; God alone suffices.I am not saying this attitude is easy! On the contrary, it is something to be practiced, because every aspect of contemporary society schools us against it. We are taught to value what is large, growing, and successful. We are not taught to value what is small, shrinking, and apparently failing.

But we must remember that we are not to be conformed to the world, but to be transformed by the renewing of our minds, and that Christ’s strength is made perfect in our weakness. And, we must remember that the relative size of the church is not about us – it is about God, and God’s people. We happen to care about it in our generation, but ultimately this is not our show.

Cultivating an attitude of holy indifference, in which we care most about is whatever is true in God’s sight, and not whatever will gain us praise in the world, is the work of a lifetime. Ultimately it is spiritual work. For good or ill, it appears that church data trends will give us plenty of opportunities to practice the attitude of holy indifference.

But holy indifference is only one of the two attitudes that are crucial in this engagement. The other is passionate curiosity. And passionate curiosity is just as important as holy indifference. Without it, holy indifference degenerates into apathy and the sin of acedia.

Passionate curiosity sees church data trends and tries to learn something new. Passionate curiosity doesn’t just accept trends, but asks the critical questions: When? Why? How? Who? Where? What?

- When was the turning point when the church stopped growing in relation to overall population and started declining?

- What was going on around that point in time, both internally and historically?

- Why might the tide have turned at that point – internal issues? external issues?

- Where are the churches that have bucked the trend?

- Why might they be bucking the trend? What are they doing differently? What is happening around them?

- How can we learn about current population trends? Where is population growing and declining overall?

- Where are people spending time today (the Internet!) that they didn’t spend time before?

- How can we engage people where they are?

- What might we need to change to make disciples today?

- How can we experiment with new possibilities without doing harm?

- And – most critically – which of these questions (and other potential questions) are worth answering?

None of these are easy questions to answer. They require research, analysis and critical thinking. They require making intentional choices. They require an input of resources: of intelligence, of time, probably of money.

To the best of my knowledge there is no entity in the Episcopal Church (or in my diocese) examining questions like these in any coordinated and methodical manner.

We are better at holy indifference in the church than we are at passionate curiosity, and that is a shame and a scandal. The God who came to earth in Christ was surely dead set (you should forgive the pun) on accomplishing the salvation of humanity. Only passionate curiosity will enable the church to accomplish the tasks he gave us: to love the world in his name, and make disciples of all the nations.

Holy indifference comes first, because it is the spiritual attitude we must cultivate as disciples of Jesus. Passionate curiosity comes second, because it is the practical attitude we must engage as evangelists today. (If you squirm at the word “evangelist” then reclaim it; it means “bearer of good news.”)

Holy indifference and passionate curiosity are equally necessary for practicing Christians in the 21st century. Neither is easy. But both will engage you heart, mind, and soul – in the love of God, in the abundant life.

Even if the data is depressing, I can’t imagine anything more fun.

* * *

Next up in the series: Given these attitudes, what practical steps can we take to track data, and when should we just not bother?

* * *

Question for you: how do you deal with depressing data? Does this help at all?

Member discussion